Emperor penguin populations declining faster than expected

Emperor penguin populations in Antarctica have shrunk by almost a quarter as global warming transforms their icy habitat, according to new research on Tuesday that warned the losses were far worse than previously imagined.

Scientists monitoring the world's largest penguin species used satellites to assess sixteen colonies in the Antarctic Peninsula, Weddell Sea and Bellingshausen Sea, representing nearly a third of the global emperor penguin population.

What they found was "probably about 50-percent worse" than even the most pessimistic estimate of current populations using computer modelling, said Peter Fretwell, who tracks wildlife from space at the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

Researchers know that climate change is driving the losses but the speed of the declines is a particular cause for alarm.

The study, published in the journal Nature Communications: Earth & Environment, found that numbers declined 22 percent in the 15 years to 2024 for the colonies monitored.

This compares with an earlier estimate of a 9.5-percent reduction across Antarctica as a whole between 2009 and 2018.

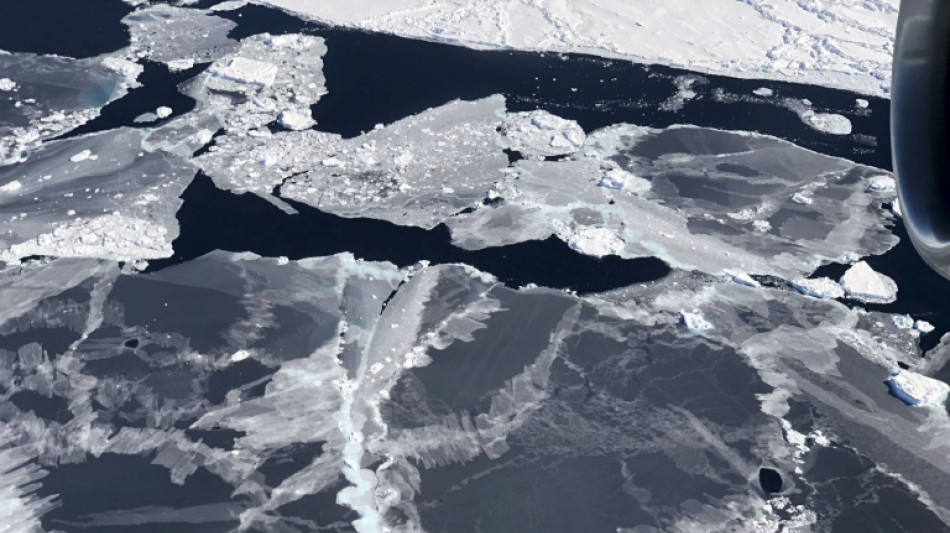

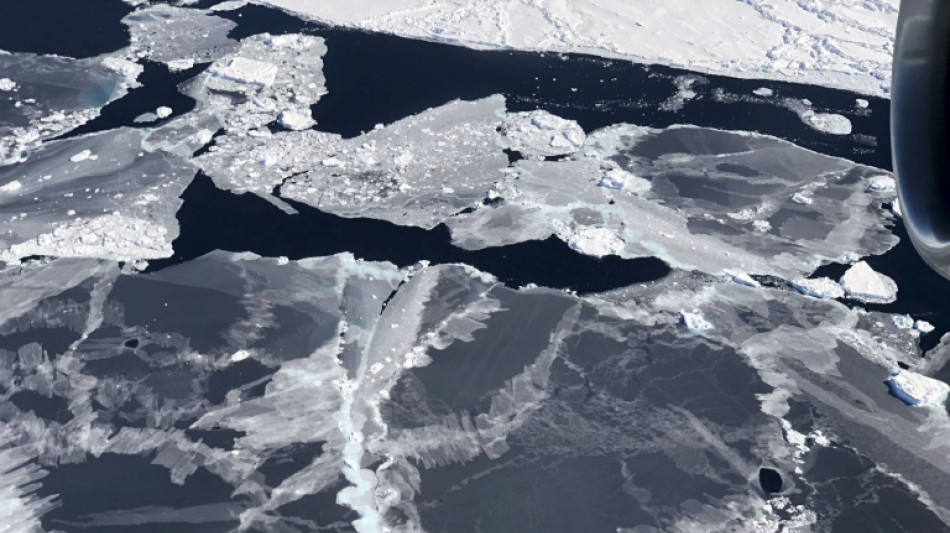

Warming is thinning and destabilising the ice under the penguins' feet in their breeding grounds.

In recent years some colonies have lost all their chicks because the ice has given way beneath them, plunging hatchlings into the sea before they were old enough to cope with the freezing ocean.

Fretwell said the new research suggests penguin numbers have been declining since the monitoring began in 2009.

That is even before global warming was having a major impact on the sea ice, which forms over open water adjacent to land in the region.

But he said the culprit is still likely to be climate change, with warming driving other challenges for the penguins, such as higher rainfall or increasing encroachment from predators.

"Emperor penguins are probably the most clear-cut example of where climate change is really showing its effect," said Fretwell.

"There's no fishing. There's no habitat destruction. There's no pollution which is causing their populations to decline.

"It's just the temperatures in the ice on which they breed and live, and that's really climate change."

- 'Worrying result" -

Emperor penguins, aka Aptenodytes forsteri, number about a quarter of a million breeding pairs, all in Antarctica, according to a 2020 study.

A baby emperor penguin emerges from an egg kept warm in winter by a male, while the female in a breeding pair embarks on a two-month fishing expedition.

When she returns to the colony, she feeds the hatchling by regurgitating.

To survive on their own, chicks must develop waterproof feathers, a process that typically starts in mid-December.

Fretwell said there is hope that the penguins may go further south in the future but added that it is not clear "how long they're going to last out there".

Computer models have projected that the species will be near extinction by the end of the century if humans do not slash their planet-heating emissions.

The latest study suggests the picture could be even worse.

"We may have to rethink those models now with this new data," said Fretwell.

"We really do need to look at the rest of the population to see if this worrying result transfers around the continent," he added.

But he stressed there was still time to reduce the threat to the penguins.

"We've got this really depressing picture of climate change and falling populations even faster than we thought but it's not too late," he said.

We're probably going to lose a lot of emperor penguins along the way but if people do change, and if we do reduce or turn around our climate emissions, then then we will save the emperor penguin."

L. Araujo--JDB

London

London

Manchester

Manchester

Glasgow

Glasgow

Dublin

Dublin

Belfast

Belfast

Washington

Washington

Denver

Denver

Atlanta

Atlanta

Dallas

Dallas

Houston Texas

Houston Texas

New Orleans

New Orleans

El Paso

El Paso

Phoenix

Phoenix

Los Angeles

Los Angeles